1840 : John George ROBERTSON (1803-1862) took up the "Wando Vale" Pastoral Run.

John George ROBERTSON (1803-1862) born 1803, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland, son of William & Annie ROBERTSON,

took up the "Wando Vale" Pastoral Run in March 1840 when he came over to Portland Bay from Van Diemen's land with Dr. Isaac CORNEY and John Frederick CORNEY.

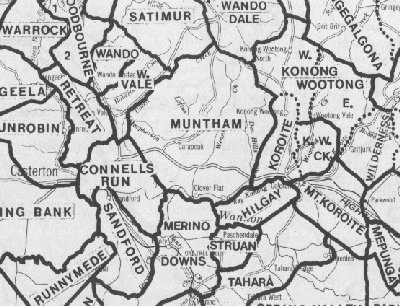

The "Wando Vale" Pastoral Run joined the "Muntham" Pastoral Run taken up by the HENTY Brothers in 1837 and occupied by Edward HENTY and his wife Anna Marie GALLIE. "Muntham" joined the other HENTY family pastoral runs of "Merino Downs", "Sandford" and "Connells Run" as shown on the map on the right. By 1845 Edward HENTY was operating both "Muntham" and "Connells Run" stations.

Before coming to Australia, John ROBERTSON had been a botonist and naturalist with an Indian expedition for two years and for seven of the nine years he spent in Van Diemen's Land he managed Formosa Farm for Mr. R. W. LAWRENCE, the botonist. Later he sent from Victoria, dried plants to the herbarium at Kew (England), and before returning to Scotland, where he died in 1862, William MOODIE helped him pack 4000 botanical specimens which he had collected for Kew. He was constantly in correspondence with other botanists and his name is commemorated by "Ranunculus Robertsoni Benth" and "Calochilus Robertsoni Benth".

Stephan Rowan ROBERTSON, sister of John George ROBERTSON who married William CORNEY in 1846, and Mary Ann ROBERTSON, another sister, who in 1852 married her cousin, George ROBERTSON of "Warrock", Casterton, came from England to Van Diemen's Land in 1840 where they started a millenary business. The sisters came to "Wando Vale" in 1843. Another sister Charlotte ROBERTSON had married John MOODIE in Scotland in 1834, and this family arrived in Port Phillip from Scotland in 1841, and later purchased "Wando Dale" Pastoral Run in 1853.

In 1852 John George ROBERTSON married Mary McCONOCHIE from "Konongwootong Creek" Station, near Coleraine but they did not have children.

1831 : John George ROBERTSON arrived in Van Diemen's Land from Scotland.

1840, February : John George ROBERTSON arrived at Portland Bay from Van Diemen's Land

1840, March : John George ROBERTSON occupied "Wando Vale" Pastoral Run

He was the fourth settler in the Glenelg & Wannon area behind Messrs. Henty, Winter and Pilleau and occupied a run he named "Wando Vale" through which flowed the Wando River. It joining the north-west boundary of the "Muntham" run of Edward HENTY. (see above map)

1840, Dec 19 : John George ROBERTSON advertised in Van Diemen's Land

"The Cornwall Chronicle" (Launceston, Tas.) Wednesday, 23rd December 1840.

FOR SALE by Private Contract.— A Sheep Establishment in the Valley of the Wandoo, Portland Bay, consisting of one thousand of the finest and longest woolled Van Diemen's Land Ewes, now in lamb, and eight hundred Ewe and Wether Lambs, six months old ; one team of bullocks, two Milch Cows, two Mares, with Drays, and every other requisite material for an establishment of the kind. There is a substantial cottage residence, men's huts, workshop, wool shed, &c, and nine acres of land in cultivation with wheat, oats and potatoes, fenced in with a four-rail fence. For particulars apply to

J. G. Robertson.

No. 4, St. John street, Launceston, Dec. 19.----------------------------------------P.S.— Wanted by the Undersigned, three men, a hut keeper, a bullock driver, and a cook, to proceed to Portland Bay. — Apply to Mr. Noakes, Norfolk Plains, or as above.

John G. Robertson.

1852, May : John George ROBERTSON of "Wando Vale" married Mary McCONOCHIE from "Konongwootong Creek" Station

1853 September : John George ROBERTSON wrote to Governor La Trobe

|

Wando Vale, 26th September 1853.

To His Excellency C. J. La Trobe, Esq., Lieutenant-Governor, Victoria. DEAR SIR, I am in receipt of your circular by last post, and I am afraid I can give you but little information connected with the settling of our district; but if a few extracts from the store of recollection will be of any use to you, you are welcome to them, with part of my own personal narrative. I arrived in the neighbouring colony of Van Diemen's Land in the year l831, and, 1ike many of my country men, with a light purse - one half-crown and a sixpence was all my pocket contained when I landed at Hobart Town with a few fellow-passengers. After walking through the streets for some two hours, they proposed having something to eat and drink, which I could not refuse joining. After bill was checked-the little now I was left with, only sixpence - I found it would not do for me to keep company any longer; so I left under the pretence of seeing a friend, but in reality to look for employment, which was easily found. Next morning I left the ship for my work, and never saw any of the passengers again. I remained for nine years in Van Diemen's Land, as overseer with two different masters on their farms, and at the end of 1840 I had saved about £3,000 from hard work. About this time I learnt that one of my sisters had been recommended to come to the colony on account of bad health, and that another of them would come with her. I determined to form a home of my own, and, owing to the extravagant price of land and stock in Van Diemen's Land, I looked to this colony as the place where I ought to invest my little all. In January 1840 I bought 1,000 ewes for £1,800; a team of six working bullocks, two cows, and a horse, for :£195. Freight, stores, tools, &c., &c., cost £311. With four men at a wage of £175, I left for Portland Bay on the 17th February 1840, and had to wait near Portland for the return of the vessel. I had previously agreed with a Mr. Corney to take the half of the vessel for fear of a bad trip, so as to divide the risk. But we were fortunate. By care and attention and fine weather, we, only lost ten sheep, and a working bullock of mine had its neck broken, to replace which I had to pay £30 for another. I had no difficulty in finding a run, as the Messrs. Henty were applied to by my former employer to forward my views, and by doing so they would be conferring a favour on him. They pointed out their boundary, and I took possession of the land adjoining, as there were but three settlers here before me - Messrs. Henty, Winter, and Pilleau. The latter had no sheep, but had taken up a run. Whyte Brothers, from the Pentland Hills, near Melbourne, came on to the Wannon country the week before I arrived, following in the track of Wedge Brothers, who stopped at the Grange, passing all that fine sheep country from Fiery Creek to the Grange, for permanent water. Messrs. Addison and Murray arrived on the Glenelg River from Portland the same day I came on the Wando, and they ran about putting up frames of huts, thinking to secure country by that means that would have kept 200,000 sheep (if they had got leave to keep it) with 700 sheep. The same week (the second in March 1840) Messrs. Savage and Dana took up Nangeela on the Glenelg; Messrs. Wrentmore and Butcher took up Warrock Station on the east bank of the Glenelg, and Messrs. Corney Brothers occupied Cashmere on the east and west bank of the Wando River; Thomas Tulloh the Wannon Falls In April following, Mr. Thomas McCulloch put himself down between Addison and Murray, Mr. Corney, and self, taking part from each, but most from me, from fear of going outside, where there was plenty of land, from fear of the natives. The same week Mr. Purbrick took part of Whyte Brothers', Pilleau's and Tulloh's. As we had all arrived from Van Diemen's Land direct, we knew nothing of the squatting regulation, and by the end of April we were all quarrelling about our boundary, and as we had no communication with Melbourne but by water occasionally, we all looked forward to the arrival of the Crown Lands Commissioner, and his duties seem at that time very ill-defined, and, owing to the conflicting testimony of the witnesses, he had a most difficult task to adjudicate. Although I had contented myself with about 12,000 acres, as there was a sort of natural boundary, by the end of June, when Crown Lands Commissioner Fyans arrived, I was left with less than 2,000 acres. And even the place where my home-station was formed was not secure. Although myself, and my neighbour, Mr. Henty, decided on a boundary when he pointed out the land to me, he, Mr. H., procured a letter from the C. L. C., for me to remove my home-station, as it was too near his boundary, which letter was not presented to me until the Commissioner had left the district. I was exceedingly anxious to get on with my improvements, and I liked the spot I had chosen. I did not consider myself justified in going on with the improvements until the return of the Commissioner six months afterwards, for fear I should have to remove my head station. By this time my quarter was about the best in the district. I had a paddock, with plenty of hay and corn for a hungry horse. When I learnt that the Commissioner was in the neighbourhood, I waited on him about twenty miles off, invited him to my place, and held out the bait of hay and corn to his horses (knowing some little of human nature); I did not forget the man as well as the horses. It had the desired effect. He promised my place the site I had chosen, told me I had been misrepresented to him, and after seeing his horses next morning, offered to extend my boundary in order to put my place in the middle of my run, which offer, to his astonishment, I declined, and by this second visit I was put in possession of my original boundary. I may here observe that the Crown Lands Commissioner made my place his quarters for nine years afterwards, and I saw a good deal of the wrangling among the squatters in this part of the district, and I may remark he had a most difficult task to perform - there was no possibility of his seeing the boundary of the different lands, and if he had, it was through thick forest, where each tried to lead him astray, and where he had never been before. His district was large, which did not admit of the time - the land was taken up so rapidly. The most conflicting evidence was given by unprincipled men, and often, I am sorry to say such matters, so that there was no getting at the truth who was the first to occupy the land. From what I have seen the C. L. C's. office was no sinecure in this district at all events. Numbers of the young gentlemen who came out to this colony about that time, with a few hundred pounds, took up runs with 300, 400, and 500 sheep, clubbed together, and expected to make fortunes in a few years, from the way they spoke, and the way in which they managed their sheep farms. Few of them knew anything of mechanics, and they were totally unable to make comfort for themselves or their servants. In consequence of which they fell back lower in morality and energy than many of their men, for dirt and filth were noticeable in places and persons, and their pride was, who would rough it best. They even went so far with their indolence as to drop shaving themselves, and it was no bad criterion to know how a man managed his station if the owner was seen looking out through a large wisp of hair on his face. The three eventful years, which will long be remembered in this colony. of 1841-2-3, swept off most of these young gentlemen with their herds and all. About twenty of the squatters in the Portland Bay District (that were fast men) were sold off. Three or four I knew compromised for less than half with their creditors, and three other large stations were so overwhelmed in debt, that they are only recovering from it now - and there is not one station, that I knew, but my own, and Addison and Murray's, in the Portland Bay District, that is occupied by the original squatter. Every station has changed hand either by dissolving partnership, letting, or selling - even that of Murray and Addison (this is the third brother of the Addisons, two having died); so that I am left the only one now that I know of. I did not feel the effect of the three bad years like most of my neighbours. I had still £500 in V. D. L. to fall back on, which all went to carry on my station by the end of 1843. With the wool of that year I bought for my cousin, Warrock Station on the Glenelg, with 2,500 sheep and team of bullocks anti all improvements, for £300. This station had been formed by Messrs. Wrentmore and Butcher for a Mr. Wilmore in V. D. Land, and cost; that gentleman £5,700, forming and keeping it for three Years. Nangeela was offered to me a few days after, with the same number of sheep, for £400, which station had been bought by the gentleman who offered it to me, at a sheriff's sale in Melbourne, for £230, the price of a dray and team of six bullocks (with the expenses of bills and law added) that had been bought for the station in 1841, and paid for by bill at the time. As I have before said, in the three years from 1840 to 1843 I had invested £3,000 in my sheep station. It is true that in that time the station had fallen in value to £300 or £400, but still the money was sunk. I did not come here as a sheep farmer with the intention of making a fortune in a few years, and leaving. I came with the intention from the first to form a comfortable home for self and two sisters, add live by the way, making and having as many little comforts within ourselves as the country could afford with frugality and industry. As a leading feature with us, we kept only one house-servant, and often none, so that the housekeeping expenses never reached £300 a year. I commenced with 1,000 sheep; at the end of five years there were 7,300 sheep on the run, and from 8,000 to 10,000 is the number I keep on it when full stocked. There are 11,810 acres of land, a pretty little station, well watered. I shall have been here fourteen years in March next, and all the cash I have taken out of the concern is £5,324, with expectations - £1,500 more in wool now coming into the London market. It is true, if my stock and station just now were sold they would bring, with purchased land and improvements, about £13,000; but if the Government resumed the land, or took it away for any purpose, the stock and station (that is, purchased land) would not be worth more than £4,000, so that I have worked hard for fourteen years for £11,824, and £3,000 of this sum was money invested. I may here mention that £4,324 of the above money was given away, as it was saved, to relatives who needed it, so that I have never had money at interest since I came here. This £11,824 gives me somewhere about £845 a year, suppose my run to be required by Government, and if you deduct interest on the £3,000, at the rate of 12½ per cent., which merchants charge for money borrowed on stations, that would leave me a clear profit of £470 a year for the last fourteen years and allow only for the keep of myself and wife and for my labour, for which I received £500 a year and keep when I left V. D. Land. The above is a true statement, which I can show data for, at any time, and you may make such use as you think proper of it. There is not a station in the Portland District better managed for its size, both as regards economy and care of man and beast in it, and I have always endeavoured to live as a farmer should do with such an income. I have no doubt there are numbers here who make their stations pay better, but most of them live little better than my pig does, and this kind of sheep farmer mostly, when he goes to town, does not like to return to his station, and often spends a deal of money at taverns in town, because be has such a comfortless home. In the month of June 1840, the station that is Willis and Swanston's - Glenelg, Pigeon Ponds, Chetwynd - was taken up by Thomas Norris for a V. D. Land company of four gentlemen. Messrs. W. and A. Forlonge soil their farm of 3,000 acres in V. D. Land for 9,000 sheep, and William Forlonge went into partnership with three merchants in Hobart Town. They were to keep all the female stock until they had 100,000 sheep; sell the male stock - the manager Norris to have £500 a year, and 10 per cent. on the sale of stock. Two of the merchants turned out men of straw; the other, Mr. Thomas Winter, told me he had £9,000 in cash to keep the station going for two and a half years, and Mr. Winter came over in the winter of 1843 to try what he could do to recover his money. They sent 4,000 sheep to Hobart Town, but they hardly paid the freight. He then left, to sell the place, when he found he could not carry it on for want of money, and the splendid run with 20,000 sheep was sold to the merchants in Hobart Town for £1,900, and it required all the purchase money to pay the liabilities, so that poor Mr. Winter lost all his £9000. Mr. Forlonge lost all his sheep. To show the reckless way business was managed in those days, William and Andrew Forlonge were partners in some purchased land near Melbourne; W. Forlonge only, in the sheep station above. William offered Andrew his share of this sheep station for the share in the land near Melbourne, which was accepted by Andrew, and it was not until Mr. A. Forlonge arrived as far as my place to arrange with Mr. Winter, that he learnt it was sold to pay the debts of the station, and delivered only the day before he came here. This was partly to be attributed to the want of postal communication, as I have before remarked, for our letters were sent from here to V. D. Land, and from thence to Melbourne, in those days. In October of 1841 Messrs. Jackson and Gibson from Melbourne came on the remaining unoccupied land on the right and left banks of the Glenelg, between Warrock on the right and Nangeela on the left, as far up as the company stations of Winter, Forlonge, and others, thus fourteen miles on both sides of the river. This was the farthest west station for two years. In the Gibson family there were two ladies (on the verge of the wilderness), one of them an old lady of 70 years of age. Mr. Jackson left for Scotland, leaving his station in charge of a Mr. Bell, who occupied the Dergholm Station on the west bank, Mr. Gibson occupying the Roseneath on the east bank - about six miles apart. The ladies, Mrs. Gibson and Mrs. McFarlane, lived in tents for ten months. Mr. G. was but an indifferent manager, and had indeed hardships to encounter. Soon after they arrived they congregated a large number of natives about their place, whom they kept hanging about, doing and undoing, to keep them employed. The ladies were anxious to get a garden formed, as they had a quantity of English seeds. They got the natives to work in the garden for them, but they were expensive labour. I have gone to the station and found as many as 20 natives round the place and not one white man near the station, Mr. Gibson and his men being away splitting or doing something from home. I used to expostulate with them about the impropriety of allowing the natives to remain about the place when there was no one about but the two females. Mr. and Mrs. G. just laughed, and said they were poor harmless creatures, and the only precaution used was, Mrs. G. carried a broken three - barrelled pistol in a leather belt which she wore round her middle; this formed part of her toilet. On one occasion Mr. G. and his only available men were making hurdles, and they were in want of nails that were at the Dergholm Station, six miles off. Mrs. G., who was fond of riding, offered to go for the nails, as they were so much wanted, and to take one of the black men for a guide. They arrived at Dergholm - the six miles, Mrs. G. riding; the black man, Yarra, walking; they got 6 lbs. nails in a leather bag, which Yarra had to carry. On the way back, in a thick forest, Yarra, who was a little before on a dray track, stopped suddenly, caught the bridle of Mrs. G.'s horse' ordered her to get off and walk and he would ride. Mrs. G. had presence of mind to pull out her pistol from her belt under her shawl, and presented it at the man, who let go the bridle in a moment. With her whip she struck her horse, which dashed off, and saved her life. Some days after, Yarra brought home the nails, and they all laughed at the affair (which they toll me some nights after), though there was nothing there to laugh at. A few days after this, Mrs. McFarlane was in the garden with some of her poor black creatures (as she called them), and she was reproving, one of them for pulling up the young potatoes. Yarra came running at Mrs. McFarlane with an uplifted rake, evidently to strike Mrs. McF., when Mrs. G. heard the scream, and rushed out with the pistol in her hand. All the natives, nine or ten of them, leaped over the fence and were no more seen. In the evening, the shepherd at the home - station did not come home; his dog brought about 300 sheep long after dark. Mr. G., the only man about the place, next morning went in search of his shepherd and sheep; the poor dog went direct to the dead shepherd, about a mile from home. Mr. G. had to walk about six miles to Bell's, for his own horses were away. Mr. Bell had one man, and Mr. G. tracked the sheep through a long heath towards the Wando, and they found about 500 sheep coming back again, which they had to return with. Mr. Bell rode 21 miles for me and two others; we all got to Roseneath about three in the afternoon. Mr. G. returned with the 500 sheep about the same time; still 700 away. Five of us started, leaving Mr. G. to take care of the ladies, as they had been thus without the least protection all day, and now became afraid to stop by themselves all night with the dead shepherd. After a smart ride of fourteen miles we came on the main body of the sheep, but no natives. The sheep were nearly all dead; such wanton destruction no one but those who saw it can imagine. There were 610 fine ewes just about to lamb, for which 42s. a head had been paid the year before - all dead; some skinned; others skinned and quartered; some cut open and the fat taken out and piled in skins, but most of them just knocked on the head with a stick; meat, fat, and all mixed with the fine sand of the stringy-bark forest. It was quite evident the natives had left in the morning, for all was cold, and we saw no cooking or cooked meat. We agreed to all ride back for two miles, taking the few living sheep with us, and one man being left with the horses, to creep back after dark, and shell all remain; but no natives came. We returned to Roseneath in the morning, buried the shepherd, and six of us started in search of the natives, but never found any of them for two days. I was out on the third night; two of our horses got away; one of them was mine, and I had to walk home, which I was afterwards very glad of, for the party fell in with an unfortunate native and ran him down, and I believe shot him in retaliation (and I now have no doubt he never heard of Mr. G.'s sheep). On my way home I came to an out-station hut of my neighbour's for a drink of water, and there was our friend Yarra, the native, chopping wood for the hut-keeper. I looked at him closely, and I saw a pair of Mr. G.'s old trousers he had on at the time all smeared with blood, whether the poor shepherd's or the sheep's I know not. I was only a mile from home, and there I found Mr. Gibson's bullock-driver with his team and two men, splitters, returning from Portland on his way home. I told the bullock-driver what had happened, and that I saw Yarra at the hut, and if he could take Yarra on with him in the morning in his dray, he might perhaps tell who had killed the shepherd. They called friend Yarra, and easily induced him to go with them, but when he came in sight of the station he got off the dray and was running away, when one of the splitters shot him. So ended poor Yarra. After this, there was a constant war kept up between the natives and the into stations - Bell's and Gibson's - and, I regret to say, a fearful loss of life to the poor natives by two young heartless vagabonds Gibson and Bell had as overseers when they left. The first day I went over the Wando Vale Station to look at the ground I found old Maggie (that Sir Thomas Mitchell gave the tomahawk to) fishing for muscles with her toes, in a waterhole up to her middle, near where the Major crossed that stream. Poor old Maggie died about fourteen days since - a dreadful sufferer from rheumatism; nearly all her male relatives were killed three days before I arrived on the Wando by Whyte Brothers. Three days after the Whytes arrived, the natives of this creek, with some others, made up a plan to rob the new comers, as they had done the Messrs. Henty before. They watched an opportunity, and cut off 50 sheep from Whyte Brothers' flocks, which were soon missed, and the natives followed; they had taken shelter in an open plain with a long clump of tea-tree, which the Whyte Brothers' party, seven in number, surrounded, and shot them all but one. Fifty-one men were killed and the bones of the men and sheep lay mingled together bleaching in the sun at the Fighting Hills. It must have been a great relief to me and most of this part, for the females were mostly chased by men up the Glenelg, and the children followed them. This I learnt since from themselves. The man who escaped was afterwards known as "Long Yarra" - a very fine-looking man. He afterwards lived for some time With a Mr. _____, a settler, who had taken a fancy to Yarra's gin, Lewequeen. There had been some very unpardonable conduct on the part of Mr. ____, who, I was of opinion, was at times deranged. In the autumn of 1843 Mr. ____ and his man Larry went to strip bark, taking a bullock-dray, Long Yarra and another native with them, about eight miles back on the Adelaide road, intending to stop out all night. As soon as they were gone, Lewequeen went away, taking her child with her, and did not return, and on the third day the shepherd put his flock in the pen and came for us. We went out, following the track of the dray, and came on the dead body of Larry, with two eagles pecking the remains of his skeleton, and at a short distance Mr. ____. They had been in bed when they were attacked, and a frightful struggle they must have had, for Mr. ____ was a very strong man. It was evidently a concerted affair, there being a number of natives, and Lewequeen leaving the shepherd's wife, which she had not done before. Mr. ____, of ____, on the Glenelg run, near me, kept a harem for himself and his men. The consequence was, he, like many more, had to sell out. All the men and masters got fearfully diseased from these poor creatures; they, of course, quarrelled with the natives about their gins, and the natives, to be revenged for some of the insults, took away 48 ewes and lambs and they were followed by some of the neighbours and Mr. ____'s own men. They rushed their camp, shot two of the natives, one of them a female, said to be Mr. ____'s foremost black woman. All the sheep were dead, which they burned, and one of the neighbours who was out brought with him to my house for the night a native basket or Been-ak, with all the female paraphernalia of red and white clay to paint, a flint, two dead frogs, some shells, and a very neat female foot half-grilled, with a large mouthful taken out of the hollow part of the foot. My neighbour brought these to me, as he said he knew I was curious about such things. In the end of 1843 I was passing through the run, and came on a black lad crying, with his face fearfully scalded. I asked him how it happened. All I could get out of him was, "George had thrown a pot of tea in his face." I took him home with me, and dressed his face with lime-water and oil; he felt grateful for what I had done for him, and he was the first I ever allowed about my place, and he and his wife and child are the only ones ever employed by me They have been with me ever since, and I give them 12s. a week and two rations. He is always very clean; but the woman, Jenny, is never clean. The native lad Joe told me he was defending his gin, which he had just got, from the man George, a bullock-driver, when he pitched the scalding tea in his face, and this man was the terror of all the fighting men on the Glenelg. About this time Mr. McCulloch parted with his overseer, who was too quiet and short-sighted, and always lost himself in the bush; he was stopping with Mr. Corney until he had an opportunity of returning to V. D. L. He went out gathering mushrooms, about 800 or 900 yards from Mr. Corney's house; he had a red handkerchief gathering them in, when a native started up a few yards from him, asked his name, and he said "George"; immediately another rose behind him, and spoke to the front native, who, dashing a spear at Mr. Lewis, struck him on the breast; he turned, and now another spear struck him on the shoulder-blade, and about four inches of the spear broke close off in the wound, which we had to open up, and we took out the spear with a pair of pliers. The poor man was very ill afterwards, but, I think, as much frightened as hurt; he used to say in his sleep that the men were eating, him, which he seemed to have a great horror of; he often used to say if he had called himself " Lewis " instead of "George" the natives would not have touched him. This is the only outrage I have known of, where the whites were not the first aggressors, or that the natives had not theft in view. In all my rambles I have never seen but five natives in a state of nature. I have never thought them numerous. I am sure I have never seen 500 all put together from the Grampians to the sea. I do not mean to say that there were not more, for if I were to believe what I have heard of as having been killed in different affrays with the settlers, they would amount to more than that number. I have on four different occasions, when they committed murders, gone out with others in search of them, and I now thank my God I never fell in with them, or there is no doubt I should be like many others, and feel that sting which must always be felt by the most regardless of the deed done to those poor creatures; and in twenty years more there will not be one in the Portland District. There are now but two settlers in the Portland District that I know who have been severe on the natives, and they are doing little good. It seems strange none have done any good who were murderers of these poor creatures - either man or master. I will here change the subject, for it is too painful to dwell on, and I cannot see the way it could be avoided, for no law could have protected these poor people from such men as we had to do with at that time. When I arrived through the thick forest-land from Portland to the edge of the Wannon country, I cannot express the joy I felt at seeing such a splendid country before me where my little all that I was driving before me was to feed. The whole of the Wannon had been swept by a bush fire in December, and there had been a heavy fall of rain in January (which has happened, less or more, for this last thirteen years), and the grasses were about four-inches high, of that lovely dark green; the sheep had no trouble to fill their bellies; all was eatable; nothing had trodden the grass before them. I could neither think nor sleep for admiring this new world to me who was fond of sheep. I looked amongst the 37 grasses that formed the pasture of my run. There was no silk grass, which had been destroying our V. D. L. pastures, where I had watched its progress with uneasiness, and I wrote to my friends there that I had never been able to detect any of this noxious grass. The fire had been so great that one could not get as much grass as would thatch our hut; we were obliged to take large cut tail-grass out of the waterholes. The sheep thrived admirably, and with a little care were clean from the scab, and I did know that there was such a thing as clean sheep. The few sheep at first made little impression on the face of the country for three or four years; the first great change was a severe frost, 11th November 1844, which killed nearly all the beautiful blackwood trees that studded the hills in every sheltered nook - some of them really noble, 20 or 30 years old; nearly all were killed in one night; the same night a beautiful shrub that was interspersed among the blackwoods (Sir Thomas Mitchell called it acacia glutinosa) was also killed. About three weeks after these trees and shrubs were all burnt, they now sought to recover as they would do after a fire. This certainly was a sad chance; before this catastrophe all the landscape looked like a park with shade for sheep and cattle. Many of our herbaceous plants began to disappear from the pasture land; the silk-grass began to show itself in the edge of the bush track, and in patches here and there on the hill. The patches have grown larger every year; herbaceous plants and grasses give way for the silk-grass and the little annuals, beneath which are annual peas, and die in our deep clay soil with a few hot days in spring, and nothing returns to supply their place until later in the winter following. The consequence is that the long deep-rooted grasses that held our strong clay hill together have died out; the ground is now exposed to the sun, and it has cracked in all directions, and the clay hills are slipping in all directions; also the sides of precipitous creeks - long slips, taking trees and all with them. When I first came here, I knew of but two landslips, both of which I went to see; now there are hundreds found within the last three years. A rather strange thing is going on now. One day all the creeks and little watercourses were covered with a large tussocky grass, with other grasses and plants, to the middle of every watercourse but the Glenelg and Wannon, and in many places of these rivers; now that the only soil is getting trodden hard with stock, springs of salt water are bursting out in every hollow or watercourse, and as it trickles down the watercourse in summer, the strong tussocky grasses die before it, with all others. The clay is left perfectly bare in summer. The strong clay cracks; the winter rain washes out the clay; now mostly every little gully has a deep rut; when rain falls it runs off the hard ground, rushes down these ruts, runs into the larger creeks, and is carrying earth, trees, and all before it. Over Wannon country is now as difficult a ride as if it were fenced. Ruts, seven, eight, and ten feet deep, and as wide, are found for miles, where two years ago it was covered with tussocky grass like a land marsh. I find from the rapid strides the silk-grass has made over my run, I will not be able to keep the number of sheep the run did three years ago, and as a cattle station it will be still worse; it requires no great prophetic knowledge to see that this part of the country will not carry the stock that is in it at present - I mean the open downs, and every year it will get worse, as it did in V.D.L.; and after all the experiments I worked with English grasses, I have never found any of them that will replace our native sward. The day the soil is turned up, that day the pasture is gone for ever as far as I know, for I had a paddock that was sown with English grasses, in squares each by itself, and mixed in every way. All was carried off by the grubs, and the paddock allowed to remain in native grass, which returned in eight years. Nothing but silk-grass grew year after year, and I suppose it would be so on to the end of time. Dutch clover will not grow on our clay soils; and for pastoral purposes the lands here are getting of less value every day, that is, with the kind of grass that is growing in them, and will carry less sheep and far less cattle. I now look forward to fencing my run in with wire as the only chance of keeping up my stock on the land.

I am, Dear Sir, Source : "Letters from Victorian Pioneers", being a series of papers on the early occupation of the Colony, the aborigines, etc. Addressed by the Victorian Pioneers to His Excellency Charles Joseph La Trobe, Esq.,

Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Victoria. Published 1898

|

1854 : John George ROBERTSON sold "Wando Vale" Station to William ROBERTSON

"Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser" (Vic.) Monday, 27th February 1854.

The value of stations seem no way diminished in this district, if we may judge from the number that are almost daily changing hands at high prices. The Wando Vale station, on the Wando, with about 10,000 sheep, has been sold by Mr. J. G. Robertson, to Mr. W. Robertson, of Woodford Station, at the figure of £16,000. It is doubtless a first rate station, though considered small, and the improvements on it are of a first rate character. The terms include a cash payment of £6000. Mr. W. Robertson takes possession immediately."Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser" (Vic.) Thursday, 6th April 1854.

NOTICE.--THE undersigned being about to leave the Colony, requests that all claims against him may be handed in to Mr Trangmar, of Julia-street, Portland.

JOHN GEORGE ROBERTSON, Of Wando Vale ; April 6th, 1854.

1854 : John George ROBERTSON & his wife Mary went to Scotland.

"Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser" (Vic.) Thursday, 17th September 1863.

DIED.--At his residence, Baronald, near Lanark, Scotland, on the 4th July, John George Robertson, Esq., formerly of Wando Vale, Portland, Victoria.

1885 : Mary, widow of John George ROBERTSON returned from Scotland & died at Balmoral, Victoria.

"The Hamilton Spectator" (Vic.) 18th June 1885.

DEATH.--ROBERTSON. On the 15th inst., at her residence "Stanmore," Balmoral, Mary McConochie, relict of the late J. G. ROBERTSON, Esg., of Baronald, lanark, Scotland, in the 74th year of her age. She was a sister of J. McCONOCHIE, and was buried at Balmoral on 17th June 1885.